The date of Easter, a pivotal celebration within the Christian calendar, is determined by a complex interaction of ecological and astronomical factors. Unlike fixed holidays such as Christmas, Easter is a movable feast. It can be celebrated as early as March 22 and as late as April 25. The variable dates emerge largely from the lunar calendar’s influence on the Julian and Gregorian calculations, creating a unique interplay that both fascinates and perplexes believers and theologians alike.

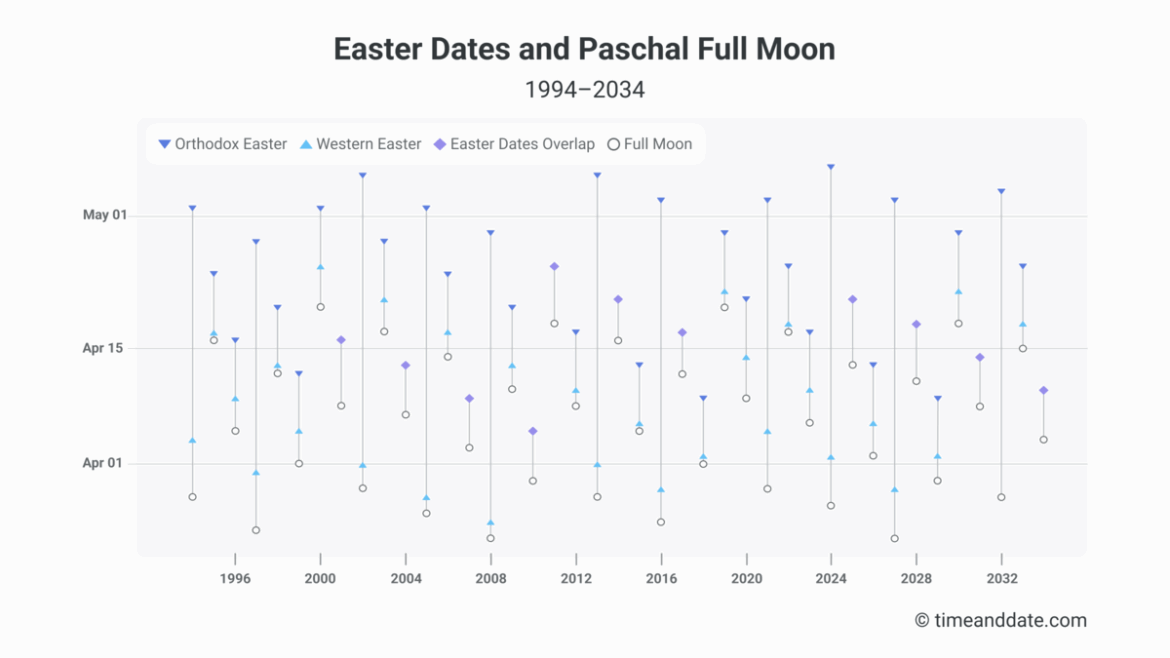

The initial step in understanding how late Easter can be involves recognizing the Church’s reliance on the Paschal Full Moon. This is the first full moon following the vernal equinox, which is fixed on March 21. Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday following this moon. This ecclesiastical approximation of the Moon’s cycles can lead to Easter being as late as April 25. The Byzantine tradition, which employs a slightly different calculation method, often causes discrepancies with Western celebrations as well.

To appreciate the earliest possible date, the scenario becomes much simpler. The earliest Easter can occur is March 22. This scenario arises when the Paschal Full Moon occurs on March 21, with Easter Sunday falling on the following day. This rare alignment is an exceptional occurrence, as Easter typically lands much later in the month.

Historically, this variation in date has significant theological implications. Different denominations place specific emphases on particular aspects of the Easter narrative. For instance, Western Christianity, including Roman Catholicism and Protestantism, often focuses on the resurrection and its implications for salvation. In contrast, Eastern Orthodox Christianity highlights the Pascha, linking its celebration closely with the underlying concepts of renewal and hope articulated in the resurrection story.

The dynamics of Easter’s timing are not solely theological but also reflect the broader context of agrarian cycles and seasonal changes. In ancient agrarian societies, spring heralded a time of renewal and fertility, which was intrinsically linked to the resurrection theme of Easter. Church authorities historically adapted to these rhythms, using them to align the faith with the natural world, further deepening the spiritual significance of the holiday.

As a result, the shifting of Easter’s date has engendered a multitude of customs and traditions across various cultures—each imbued with unique interpretations of the resurrection. Regardless of the specific timing, these customs create a tapestry of celebration globally, weaving together the historical, cultural, and spiritual threads of Christianity.

Exploring variations in the observation of Easter offers insights into its rich tradition. For example, Orthodox Christians celebrate Easter according to the Julian calendar, which is currently 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar employed by Western Christianity. The divergence often results in a later celebration for many Orthodox believers, with Easter sometimes falling into May. These cultural practices foreground the belief and perception surrounding the resurrection, resonating deeply in communities around the world.

As society progresses into an increasingly secular world, the historical and theological significance of Easter’s timing continues to evolve. Some contemporary interpretations emphasize Easter as a symbol of rebirth and transform it into a more generalized celebration of spring and renewal, often detached from its ecclesiastical origins. This shift raises questions about the future of Easter celebrations in a globalized and pluralistic context, where varying interpretations of meaning coalesce around the search for hope and renewal.

This exploration into Easter’s timing also invites consideration of how its calculation affects the liturgical year. Various denominational calendars interlace special dates and commemorations around Easter’s determination. For instance, Lent, a period of fasting and reflection, culminates in Holy Week just before Easter Sunday. The interdependence of these observances illustrates how the timing relates to larger theological narratives, grounding individuals in a rhythm of faith.

Moreover, looking at the practical implications of Easter’s timing reveals fascinating insights into church practice. Many congregations synchronize their liturgical themes and lectionary readings with the season’s overarching focus on resurrection and hope. This structure enhances communal worship experiences and deepens the congregants’ theological understanding of Easter. It encourages believers to engage with the richness of the season through confession, reflection, and celebration.

In conclusion, the complexities surrounding the determination of Easter’s date underscore its multifaceted significance within the Christian tradition. By understanding how late Easter can be, and recognizing its historical, cultural, and theological dimensions, individuals gain a deeper appreciation for this sacred time. While variations may exist across denominations and cultural practices, the core message of resurrection, hope, and renewal remains a unifying thread for Christians worldwide. The mathematical intricacies of this movable feast, far from trivial, are imbued with rich meaning that transcends mere calculation, inviting all to contemplate the profound implications of faith and rebirth.