South Africa’s apartheid, a system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination, spanned from 1948 until the early 1990s. Over this grim epoch, anti-apartheid activists and international voices rallied against systematic oppression, fuelling a moral and ethical battle that reverberated not only across the southern tip of Africa but also throughout the globe. Understanding apartheid involves delving into its laws, the resistance that emerged, and its broader legacy, particularly through a Christian lens that emphasizes justice, equity, and the inherent worth of every individual.

At its core, apartheid was a legal framework designed to maintain the dominance of the white population over other racial groups, particularly Black South Africans. The National Party, which came to power in 1948, enacted a series of laws that codified racial discrimination. The Population Registration Act classified South Africans by race, resulting in unequal distribution of land, rights, and opportunities. The Group Areas Act enforced residential segregation, forcing non-white populations into marginalised areas. The Bantu Education Act ensured that educational resources were deliberately subpar for black students. These laws interwove to create a social fabric deeply fractured along racial lines.

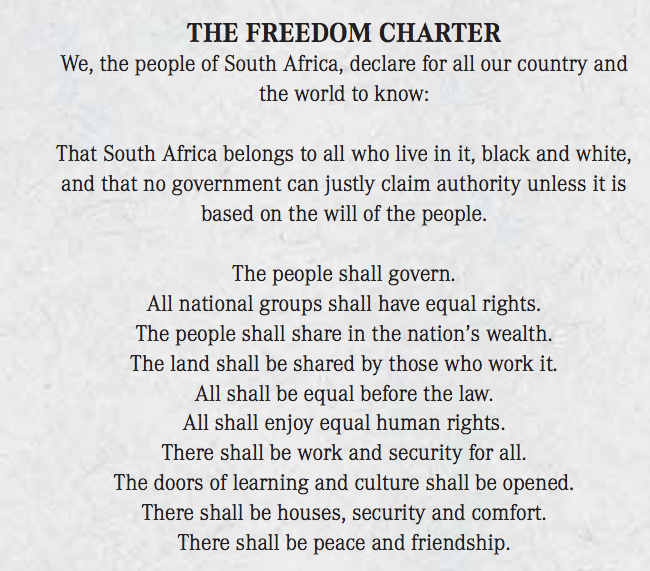

Yet, amid such oppressive structures, the seeds of resistance began to sprout. Various movements emerged to challenge apartheid laws, some grounded in Christian principles. The African National Congress (ANC) was paramount among these, advocating for equality and justice through various means, from peaceful protests to armed resistance. Christian leaders played pivotal roles, notably Bishop Desmond Tutu, who fervently appealed to the conscience of the nation and the world. He advocated for non-violent resistance, drawing upon theological principles of love and reconciliation.

As resistance grew, so did the government’s efforts to suppress dissent. Laws like the Suppression of Communism Act and the Unlawful Organizations Act criminalised opposition movements, systematically silencing voices that called for freedom and justice. Detentions, torture, and violence became the government’s tools of choice. The Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, wherein police killed 69 peaceful protesters, shocked both the nation and the world, galvanizing widespread condemnation and escalating the struggle against the regime.

The Christian community, although not monolithic in its viewpoints, largely found itself torn between complicity and resistance. Many church leaders embraced the anti-apartheid struggle as a moral imperative, citing scripture to support their positions. Biblical narratives of liberation, such as the Exodus story, resonated powerfully with those fighting for their rights. Verses calling for justice, such as Micah 6:8, became rallying cries for those challenging apartheid’s moral bankruptcy.

As the resistance movement gathered momentum, the idea of liberation theology emerged, particularly within the South African context. This theological framework emphasized the need for the church to advocate for the oppressed. It reframed the Christian mission, urging believers to act against injustice and stand in solidarity with the marginalized. Liberation theology provided a robust foundation for understanding Christian responsibility in the face of systemic evil.

In 1989, the winds of change began to sweep across South Africa, setting the stage for negotiations. F.W. de Klerk, then President of South Africa, initiated discussions to dismantle apartheid. The release of Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990 marked a momentous turning point. Mandela, a figure seen not only as a political leader but as a moral giant, embodied the potential for reconciliation and healing. His leadership style, deeply rooted in forgiveness and unity, offered a stark contrast to the bitterness that apartheid had stoked.

Ultimately, in 1994, South Africa held its first democratic elections, symbolising the end of decades of institutionalized racism. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established under Mandela’s presidency, aimed to address past atrocities and promote healing. This innovative approach to justice emphasized restorative rather than retributive measures, echoing Christian teachings on forgiveness and accountability.

The legacy of apartheid remains a complex tapestry. While the end of legal segregation marked a monumental victory in the struggle for human dignity, socioeconomic disparities perpetuated by decades of oppression still plague the nation. Many South Africans continue to grapple with the consequences of the past, as issues of inequality, poverty, and access to education linger. In this context, the church has a profound role to play, not only in providing spiritual guidance but also in advocating for social justice and economic equity.

From a Christian perspective, the apartheid era serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of systemic sin and the necessity for vigilance against injustice. It illustrates the danger of silence in the face of oppression and the moral imperative to stand up for the oppressed. As society reflects on this painful chapter in history, there is an urgent need for a renewed commitment to the values of love, equality, and justice—principles deeply rooted in Christian teachings.

In conclusion, understanding apartheid transcends a historical recounting; it involves a deep moral inquiry into how faith and ethics intersect with social justice. The struggle against apartheid not only reshaped South Africa but also offers invaluable lessons for current and future generations. As communities around the world grapple with their own issues of injustice and inequality, the South African experience reminds us of the enduring power of collective action, moral clarity, and the pursuit of a just society based on love and respect for all individuals.