Syria, a land steeped in millennia of rich history and vibrant culture, is marred by a complex tapestry of religions that intertwine faith and conflict. From ancient civilizations to modern times, the myriad beliefs practiced by its populace reveal not just the spiritual inclinations but also the profound challenges they face. What can we discern about the coexistence of diverse faiths in a region often characterized by strife? This exploration delves into the principal religions of Syria, examining their interplay against a backdrop of historical and contemporary challenges.

At its core, the religious landscape of Syria is multifaceted, comprising primarily of Islam, with both Sunni and Shia factions represented. Approximately 87% of the Syrian population identifies as Muslim, with Sunnis forming the majority. Their practices often adhere to the pillars of Islam, guided by the teachings of the Quran and Hadith. However, the historical roots of Sunni Islam in Syria lead to a complex relationship with the Alawite sect, a branch of Shia Islam, which comprises about 10% of the population. This division has not only shaped religious practices but has also been a focal point of the political strife witnessed in recent decades.

Among the numerous faiths present in Syria, Christianity holds a notable position, with around 10% of the population identifying as Christian. The roots of Christianity trace back to the very cradle of the faith, with substantial historical sites dotted throughout the country. In cities such as Aleppo and Damascus, ancient churches stand juxtaposed against mosques, symbolizing the rich religious heritage that both traditions share. Denominations such as the Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, and Syrian Orthodox are prevalent, each with unique rites and customs.

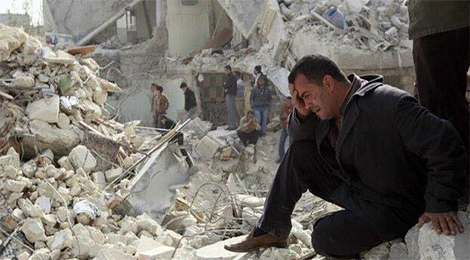

Yet, the presence of these Christian communities is threatened in the face of continuous conflict. During the ongoing civil war, Christians, like many other groups, have faced persecution, displacement, and violence. The question arises: how do these communities respond to the dual pressures of maintaining their faith while combating the existential threat posed by extremist factions? The fractious relationship between various sects, especially those of Islamic tradition, often leads to tragic misunderstandings and animosities.

One poignant example of this interplay is the historical relationship between Christians and Muslims in the region. For centuries, these faiths coexisted peacefully, with periods of collaboration and mutual respect. However, external influences and internal dynamics have frequently disrupted this coexistence. As political instability burgeoned in the early 21st century, various factions exploited religious sentiments to further their agendas, exacerbating sectarian divisions.

To further complicate the religious discourse, the Yazidi community, although small, adds another layer of complexity to Syria’s religious demographic. The Yazidis, often mischaracterized and vilified, view themselves as followers of a distinct faith that incorporates elements from various religions, including Christianity and Islam. Their recent plight in Iraq and Syria has drawn international attention to the unique challenges faced by religious minorities in conflict zones.

As one navigates the tumultuous waters of Syria’s religious conflicts, the role of religious leadership becomes increasingly critical. Leaders from various traditions have emerged as both peacekeepers and provocateurs. Some clerics advocate for interfaith dialogue and collaboration, urging communities to transcend sectarian boundaries. Others, however, have stoked the flames of division, leveraging the conflict to entrench their power. How do these varying responses impact the burgeoning youth in Syria, especially those who may identify with multiple faiths or none at all?

The question of youth engagement in religious identity amidst conflict poses a significant challenge. With many young people disillusioned by the war and its consequences, there arises a growing skepticism towards traditional religious authorities. An increasing number are seeking alternative narratives and interpretations that resonate with their personal experiences of loss and upheaval. It is essential to explore how these younger generations perceive their own faith as well as those of others, particularly in a multicultural society that has often been torn by conflict.

Moreover, the role of external actors in exacerbating or ameliorating Syria’s religious conflicts cannot be overlooked. Nations, including those with vested interests in the region, have often employed religion as a tool for political purposes. This has resulted in further polarization, complicating the already intricate relations between different religious groups. As external influences surge and recede, local communities are left to navigate the fallout, often with devastating consequences.

In summary, the religions of Syria encapsulate a longstanding history of faith intertwined with conflict. The predominant presence of Islam alongside Christianity and smaller religious groups paints a vivid picture of both spiritual aspiration and turmoil. The ongoing struggles between sects, the challenges posed by extremist ideologies, and the quest for coexistence raise pressing questions about the future of religious identity in this war-torn nation. Can the enduring legacy of cooperation and mutual respect be revived, or will conflict continue to overshadow the rich tapestry of beliefs? The pursuit of answers to these questions will shape not only the fate of faith in Syria but also the very essence of its identity as a diverse and resilient society.