What language is South Africa? This question might seem straightforward at first; however, it conceals layers of complexity that reflect the nation’s rich tapestry of cultures and histories. South Africa is uniquely defined by its eleven official languages, a fact that illuminates both the diversity of its populace and the intricate dynamics of communication in a post-apartheid society. Each of these languages carries its own cultural significance, allowing for a kaleidoscopic interaction among its speakers. In this exploration, we will analyze the linguistic landscape of South Africa while considering its implications from a Christian perspective.

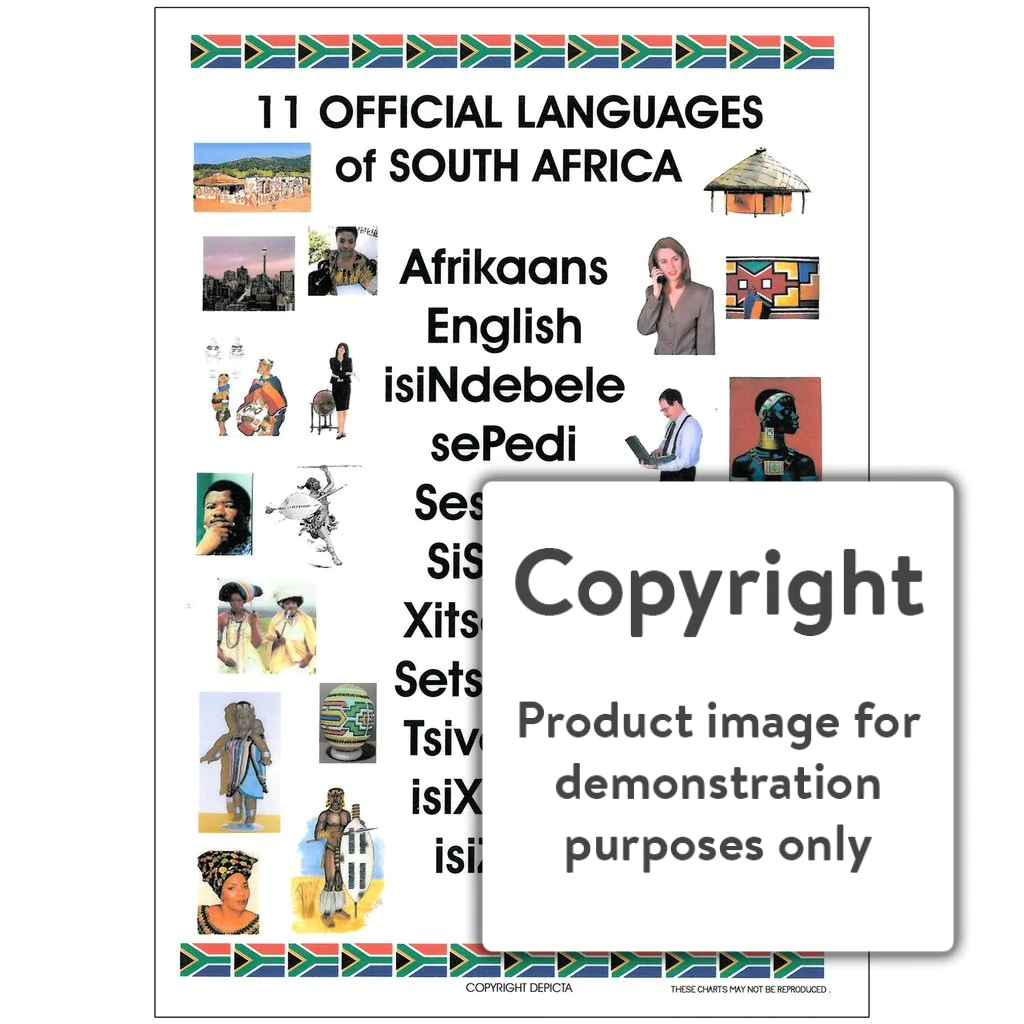

South Africa’s eleven official languages are as follows: Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, sesotho sa Leboa (Northern Sotho), seTswana, siSwati, and Tshivenda. Additionally, xiTsonga rounds out this remarkable linguistic spectrum. At the heart of this inquiry lies an intriguing challenge: how do these diverse languages coexist, and what do they reveal about the nation’s identity, particularly through the lens of Christianity?

Firstly, Afrikaans and English dominate many urban settings, each language enveloped in rich history. Afrikaans, with roots in Dutch, burgeoned during the 17th century and has evolved into a language replete with cultural nuances and regional dialects. Conversely, English serves as a global lingua franca, often bridging the gaps between various language speakers, allowing for broader communication on theological matters. Christianity, which has substantially influenced South African culture, often finds commonality within these two tongues, especially in church services and religious literature. The merging of English hymns and traditional Afrikaans songs illustrates how these languages can harmoniously coexist, fostering a shared spiritual community.

Upon examining the indigenous languages, one may recognize isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, seTswana, and others as vital conduits of cultural expression. These languages encapsulate the essence of local customs and traditions, often reflecting biblical narratives and spiritual teachings in deeply resonant ways. For instance, isiZulu and isiXhosa are lauded for their expressive proverbs and oral traditions that narrate moral stories akin to parables found in the scriptures. This native vernacular offers an interesting lens through which churches can engage local communities, enabling congregants to connect more profoundly with the messages being shared.

Imagine attending a Sunday service where one could choose to participate in prayers and songs not exclusively in English or Afrikaans, but in their mother tongue. How inviting would that be? This inclusivity challenges our understanding of religious practice in a multicultural society while promoting unity amongst diversity. As South African Christians navigate the path to spiritual growth, the utilization of local languages in worship serves to embrace the biblical message that “every nation and tribe” will be represented in God’s kingdom (Revelation 7:9).

Furthermore, the interplay of languages within Christianity in South Africa can enrich theological discourse. The interpretation of scriptural texts in multiple languages opens doors to different understandings and offers fresh insights that may be lost in translation. For instance, the phrase “Love thy neighbor” can take on unique significance and interpretation through the rich vocabulary of isiXhosa, a language that emphasizes community and interconnectedness. Thus, the multi-linguistic character of South Africa not only celebrates diversity but enhances the overall richness of the spiritual dialogue.

However, the presence of eleven languages also poses practical challenges within the church and society. How can a single congregation address the varied linguistic needs of its members without alienation? This dilemma may lead some to question whether inclusivity actually risks diluting the church’s message. Would it be easier to conduct services entirely in one language? Yet, such a strategy might disenfranchise many individuals, ultimately undermining the core Christian tenet of embracing all people.

Communities are encouraged to rise to this challenge through innovative solutions that harness technology and creativity. For instance, using translation apps or live subtitling during services can facilitate understanding. Moreover, multilingual praise and worship teams combining various languages can evoke a sense of unity and celebration, symbolizing the body of Christ in its entirety.

In addition to enhancing interpersonal communication, the official recognition of multiple languages can foster greater social cohesion. Historical context demonstrates that languages often encapsulate social stratifications. Therefore, the Christian community must acknowledge and advocate for language rights, further demonstrating the love of Christ through social justice. By affirming the intrinsic value of each language and its speakers, the church can transact an important message of dignity and respect.

In conclusion, the eleven official languages of South Africa summarize the kaleidoscopic identity of the nation. They incite questions regarding communication, inclusivity, and social justice from a Christian perspective. The challenge posed by this diversity calls for creativity, adaptation, and profound respect for linguistic heritage within spiritual contexts. The exploration of language in South Africa leads believers to a greater appreciation of God’s intricate creation, a multilingual celebration of faith that embodies the principle of unity amid diversity. As we reflect on the range of languages in South Africa, may we envision a church that flourishes in multiplicity, reverberating the divine mandate that encourages all to partake in the fellowship of love, regardless of the tongue they speak.